What Lenses do you Need for Wildlife Photography?

“A lens, a lens! My kingdom for a lens!”

My NIKKOR 600mm lens

Size isn’t everything, as they say, but there’s nothing like the power, reach and feel of a long lens—especially if it’s a fast prime. It gets you where the action is and lets you take close-ups of skittish and possibly dangerous wild animals with beautiful background bokeh. You still need other types of lenses, of course, but they’re far less glamorous!

It’s also important to remember that a good lens can improve your photography much more than a good camera can (see article). If you’re on a budget, it’s better to spend your money on new glass than the latest all-singing, all-dancing Nikon Z8/Z9, Canon R1/R3/R5 Mark II or Sony ⍺1 II.

Here’s a quick guide to what’s in my camera bag and what should probably be in yours, bearing in mind a few key buying criteria: focal length, aperture, image stabilisation (IS), weight and price.

My Lenses

When I first started out as a wildlife photographer, I bought Nikon kit rather than Canon on the basis that I didn’t want anything made by a photocopier manufacturer! I went through the D800, D810 and D850 DSLRs and various Nikon lenses, including an 800mm (with a 1.25x TC) and an 80-400mm, various wide-angle zooms and a macro lens.

However, I wasn’t happy with the sharpness of most of those (apart from the 800mm), and I was frustrated by the lack of eye detection. As a result, I did a lot of research and decided to take the mirrorless plunge!

I ended up with a pair of Sony ⍺1 cameras and the following lenses:

The G Master series is Sony’s professional range of lenses, so buying all that glass certainly wasn’t cheap, and I needed a bank loan to do it! However, as my very first boss once said to me, you can’t do your job without the tools of the trade. I needed fast lenses at every possible focal length that were light enough for handheld shooting—and that’s what I got!

After taking photographic trips to Arviat, Antarctica, Ol Jogi, Chobe and Lake Kerkini, I was very happy with my cameras and lenses. The Sony ⍺1 is a great camera that doesn’t know the meaning of the word ‘trade-off’ (with a couple of minor quibbles)—although if you don’t have the budget or prefer Nikon or Canon, feel free to read my guide to the best cameras for wildlife photography!

My Sony lenses allowed me to take super-sharp shots in every possible environment, from the frozen tundra of Hudson Bay to the heat of Botswana in the dry season. They were all light enough for handheld shooting and offered image stabilisation (except for the wide-angles) and a wide maximum aperture of f/2.8 or f/4. The 400mm and 600mm also had focus limiters to improve AF acquisition and three different IS modes.

However, I’m always looking to get my hands on the very best equipment, and I’ve recently traded in one of my Sony ⍺1 bodies and all my Sony lenses (except the 24-70mm and the 70-200mm) for a Nikon Z8 and a NIKKOR Z 600mm f/4 TC VR S lens.

There are two good reasons for that:

Pre-release capture

Built-in 1.4x teleconverter

Pre-release capture is an absolute must for bird photography, but the original ⍺1 didn’t have it. The ⍺1 II does, as well as the ⍺9 III—but that only has a 24MP sensor.

The benefit of Pre-Release Capture is that you can buffer pictures temporarily while you’re focusing on your subject. When you finally press the shutter, the camera writes up to a second’s worth of images to the memory card.

As on the Z9, it’s limited to JPEG format—although that may change in the next firmware update. However, the great benefit is that it acts like a time machine, enabling you to take action shots that your reflexes would never have been good enough to get!

The other benefit of my new Nikon gear is the built-in 1.4x teleconverter in my 600mm lens. To me, it’s the ideal compromise between a prime and a zoom. You get the wide maximum aperture and all the optical quality of a prime, plus some of the flexibility of a zoom in terms of focal length.

I used to have 400mm and 600mm lenses, but it was a nightmare deciding which lens(es) to pack or take on game drives. Nowadays, I don’t need to pack an extra bag as I can take my 600mm lens with me wherever I go and simply flip a switch to get to 840mm!

What Type of Lens Should You Buy?

The basic decisions to make are telephoto vs wide-angle and zoom vs prime. Let’s have a look at what you really need for wildlife photography.

Telephotos

Rock, Tree, Leopard (taken with my old Sony FE 600 mm f/4 G Master lens)

Telephoto or long lenses are essential for most wildlife photography as they bring distant subjects within reach and allow you to take close-ups when they’re within a few yards. I used to love the sharpness of my old Nikon 800mm, but it was so heavy that I couldn’t possibly shoot handheld—and that was eventually a dealbreaker.

My new 400mm and 600mm are so light that you can pick either one up with your little finger! In Botswana last year, I’d fit them on my two camera bodies and take them both on game drives and boat rides alike. I’d take my other lenses with me in my camera bag, but I rarely needed to swap them out—except if I was getting up close and personal with a herd of elephants!

The 600mm was especially good for birds and distant animals while the 400mm was handy for full-length shots of animals at closer range. Both had wide enough maximum apertures that low light was never a problem.

For birds in flight, it was a trade-off. I wanted the reach of the 600mm lens (sometimes with the 1.4x teleconverter), but the restricted field of view was an issue when shooting handheld. For medium-sized birds like the lilac-breasted roller or bigger ones like the African fish eagle, I’d often use my 400mm lens and crop in later.

If you have a Nikon mirrorless camera, I recommend the lightweight NIKKOR Z 800mm f/6.3 VR S lens. It’s not very fast, but it offers more reach than my old Sony FE 600mm F4 GM Super Telephoto Lens, and it’s even lighter. If you’re a Canon user, the best is probably the RF 600mm F4 L IS USM—if you can afford it!

Wide-Angles

Feeding Frenzy (taken with my 24-70mm lens at 26mm)

When I went to Kicheche Bush Camp a couple of years ago, the part-owner and wildlife photographer Paul Goldstein couldn’t believe I hadn’t brought a wide-angle. I had to explain that I just didn’t tend to take many wide-angle shots, and I normally packed light. However, the lesson there was that perhaps I should be taking more wide-angle shots, so I won’t make that mistake again!

Wide-angle lenses give you the option of including a broader field of view. This comes in handy when you have a large, close subject such as an elephant or when you want to take an environmental portrait in which the subject occupies only a small part of the frame. Wide-angles can also be used to exaggerate perspective and distort angles, which can work with extreme close-ups.

To cover all the possible bases, I have zooms that cover every focal length from 12mm to 200mm. However, the only time I really need the 12-24mm is when I’m taking pictures of the rooms at a safari lodge!

The 24-70mm was again ideal for interior shots, but I didn’t really get a chance to use it in Kenya or Botswana. There weren’t many open plains, so I couldn’t try to take the classic shot of an elephant with a stormy sky in the background. There were too many trees in the way, and the weather was too good!

The 70-200mm came in handy for photographing elephants on boat rides in Botswana, giving me the flexibility to zoom in close or zoom out to get full-length shots of the animals taking dust baths on the banks of the river. It was no good for the African birds, but it was ideal for the pelicans on Lake Kerkini.

If you have a Nikon mirrorless camera, you could try the NIKKOR Z 14-24mm f/2.8 S or the NIKKOR Z 24-70mm f/2.8 S. Canon mirrorless users have the RF 15-35mm F2.8 L IS USM and the RF 24-70mm F2.8 L is USM.

Zooms

Bird Bank (taken with my 70-200mm lens)

The first few lenses that I bought were all zooms because they were so convenient. I didn’t need so many lenses, which saved me money and weight, and the ability to zoom in and out was ideal for precise framing.

However, as I developed as a photographer, I realised I was missing out. Yes, zooms are much cheaper and more flexible, and there are now some excellent ones with internal zoom mechanisms like the NIKKOR Z 180-600mm f/5.6-6.3 VR and the Sony FE 200-600mm F5.6-6.3 G OSS Super Telephoto. However, you often pay the price in a narrower floating maximum aperture, poorer image quality and greater weight.

Zoom lenses are more complicated to make. That means more elements, more motors and more control systems. The extra weight of an individual lens may be worth it if it means you don’t have to carry two or three at different focal lengths, but I’d rather not compromise.

Zooms also tend to produce lower image quality. I noticed that with my 80-400mm, but it’s also partly to do with their target market. Zooms are flexible, convenient and cheap, which means they’re ideal for beginners and intermediates. If you’re looking for top-quality glass, you’re unlikely to find it in a zoom made for the mass market!

Finally, zooms are generally not as fast as primes—and that’s another compromise I wasn’t prepared to make. I ended up getting tired of reading the EXIF data for shots taken by professionals at f/2.8 or f/4 when my old Nikon lenses could only manage f/5.6!

I was losing up to two stops in higher ISO and greater depth of field, resulting in backgrounds that weren’t as buttery smooth as I wanted. That’s why I made sure all my new lenses (apart from the 600mm) had a maximum aperture of f/2.8.

I could easily have bought the Sony FE 100-400mm F4.5–5.6 GM OSS lens, but I couldn’t put up with the aperture of f/4.5-5.6. I would’ve loved to have a lens with a similar zoom range to my old 80-400mm, but that would’ve been a backward step. There’s best, and there’s second best.

If you have a Nikon mirrorless camera, you could try the NIKKOR Z 70-200mm f/2.8 S or NIKKOR Z 100-400mm f/4.5-5.6 VR S. Canon mirrorless users might want the RF 70-200mm F2.8 L IS USM, the (expensive!) RF 100-300mm F2.8 L IS USM or the RF100-500mm F4.5-7.1 L IS USM.

Primes

On the Hop (taken with my 400mm prime lens)

The first time I bought a prime telephoto lens (my 800mm), I was a bit worried about framing. I didn’t know if I’d like having no choice in the matter! As it turned out, I got used to it right away.

Something like a 600mm or 800mm is not a general-purpose lens. It’s a specialist tool for taking close-ups and reaching distant subjects. As a result, I sometimes just have to ‘accept the crop’—or switch to my other camera!

This is where having two camera bodies comes in very handy. You don’t have to worry too much about cropping your subject because you know you can always switch to a shorter lens on the other body. And if that’s still too long, you can always rummage around in your camera bag and fit a wide-angle on the fly…

Nikon still makes the 800mm for DSLRs, but it also has the NIKKOR Z 800mm f/6.3 VR S—the equivalent lens for mirrorless cameras. Canon users might choose the RF 800mm F5.6 L IS USM.

Teleconverters

White Run (taken with my 400mm lens and my 1.4x teleconverter)

The purpose of teleconverters (or ‘extenders’ if you’re a Canon user) is to give an existing lens extra reach. You lose a stop for a 1.4x converter and two stops for a 2x converter, but it’s sometimes worth it. For example, the Sony FE 300mm F2.8 GM OSS is light, fast and sharp, but a little short. However, pair it with a 2x teleconverter, and you’ve got acc an f/5.6 600mm lens!

In quite a few early game drives in Botswana, for instance, I’d pair my 600mm lens with the 1.4x converter and my 70-200mm with the 2x converter. That gave me something close to my old combination of the Nikon 80-400mm and 800mm lenses.

However, I soon began to miss being able to shoot wide open at f/2.8 or f/4, so I swapped to the 400mm and 600mm lenses most of the time.

The one thing I’d like to see from a Sony telephoto at some point is a built-in teleconverter. Ideally, it would be a 400mm f/2.8 that converted into an f/4 560mm lens or a 600mm f/4 that converted into an f/5.6 840mm lens. That would mean I could buy one and use it with a Sony ⍺1 II.

I don’t know if Sony has something like it in the pipeline, but Canon used to offer a 200-400mm f/4L IS USM Extender 1.4x, and Nikon has recently released two of them: the NIKKOR Z 400mm f/2.8 TC VR S and the NIKKOR Z 600mm f/4 TC VR S. They’re frighteningly expensive (!), but they’re ideal for wildlife photography.

Over to you, Sony…

Buying Criteria

When buying a lens, there are other factors to consider apart from the focal length or zoom range. Let’s have a look at the most important ones.

Aperture

The maximum aperture of a lens is a key characteristic. Lenses with large maximum apertures are called ‘fast’ lenses, and they help reduce the ISO in low light. The more light enters the camera, the less of a problem noise will be, so that’s another benefit.

The other reason to buy a fast lens is to reduce your depth of field. Most wildlife photographers shoot wide open to isolate the subject against a blurred background, and that’s much easier to do at f/2.8 than at f/5.6!

Image Stabilisation

Most modern lenses have image stabilisation (or ‘Vibration Reduction’ if you’re a Nikon user). If you have a mirrorless camera, you’ll probably have In-Body Image Stabilisation (IBIS) as well. This is important for reducing camera shake—especially when using a long lens.

It’s also important to turn the slider on the lens to the right setting. Most shorter lenses just have an on/off slider, but telephoto lenses usually have two or even three positions:

Position one is for normal usage.

Position two is for panning shots (to limit up and down movement).

Position three is to control large, erratic movements in every direction (eg if you’re on a boat or in a moving vehicle).

Weight

The weight of a lens is important for two reasons. First of all, a heavy lens is harder to handhold for long periods. Secondly, it uses up a lot of the weight limit for your hand luggage when flying abroad. This is especially true when you visit Africa, where the weight limit on most internal flights is only 15 kg!

The importance of weight depends on where you’re likely to do your photography. If you make regular trips abroad and like to shoot handheld on walking safaris, you’ll be worried about every pound going into your hand luggage! On the other hand, if you spend a lot of time on game drives in Africa, you can always rest your lens on the side of the vehicle, so it’s not so much of a problem.

Remember that most airlines let you take a ‘personal item’ on board the plane as well as your hand luggage. For a long time, I didn’t realise this. Fortunately, a photographer friend of mine let me in on the secret. My camera bag isn’t big enough for both my long lenses, so I thought I could only take one with me. However, I now put my 600mm in my camera bag and sling my 400mm over my shoulder. Job done!

Price

If you’re a perfectionist with a friendly bank manager (like me!), there’s no substitute for the right lens, however much it costs. However, we all have different budgets, and many people just can’t justify spending thousands of pounds on a new lens.

If you’re turned down by the Bank of Mum and Dad (!), there are a few ways of getting round this problem:

Borrow a lens.

Rent a lens.

Buy a third-party lens (such as a Sigma or Tamron).

Buy one or two zooms instead of multiple primes.

Apply for a loan.

Unfortunately, there are problems with all those alternatives:

You may not know someone willing or able to lend you a lens.

Renting a lens gets expensive for more than a couple of trips a year.

Third-party lenses are generally not as good as own-brand glass and may not support all the camera’s functionality. Sigma makes several good and affordable wildlife lenses for the Sony E-mount (eg the 100-400mm f/5-6.3 DG DN OS Contemporary, the 150-600mm F5/-6.3 DG DN and the 300-600mm F4 DG OS Sports), but there are fewer options for Canon and Nikon users.

Zooms won’t be as fast as primes, and the image quality won’t be as high.

You may not qualify for a loan or be able to afford the repayments.

Photography is an expensive hobby, so you might just have to save up for a few months (or years!) for The One Lens to Rule Them All…

Verdict

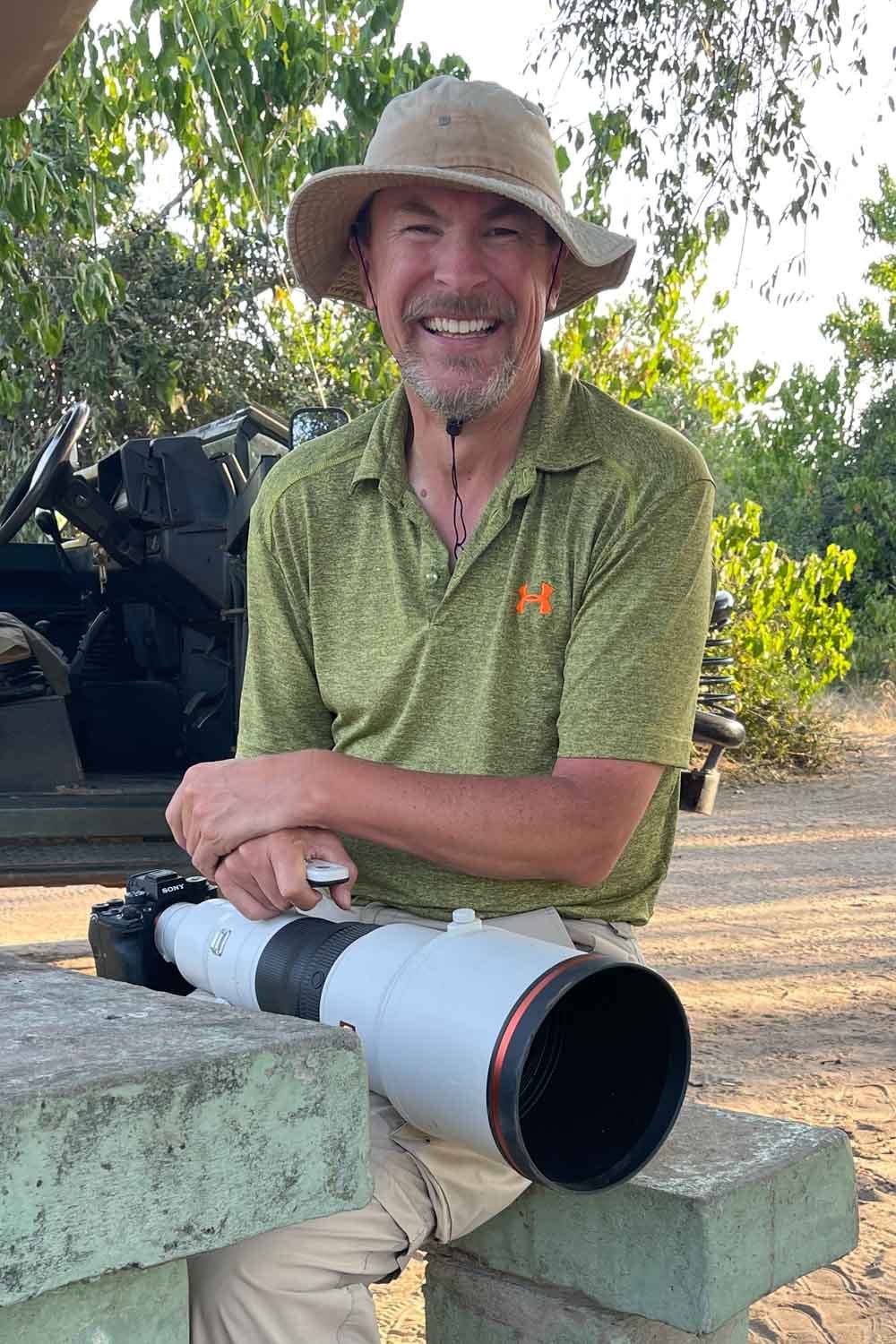

Me and my shadow…

Wildlife photography is possible with any lens (even the ones in your iPhone!), but serious photographers will want fast, light lenses covering the whole range of focal lengths—and preferably with a built-in teleconverter. Wide-angle lenses are fairly cheap, but long lenses can easily cost thousands, especially the ones with a wide maximum aperture.

For a professional or keen amateur (with a healthy bank balance!), it might make sense to buy all the best lenses. However, if you’re not in that happy position, you might need to find a way around the problem by compromising on quality or borrowing/renting something for a week or two.

It all depends on what kind of wildlife photographer you are, so it’s horses for courses. If you like environmental portraits or wide-angle close-ups, you won’t need to spend much on lenses—and zooms are the way to go.

However, if you’re in love with long-distance close-ups and creamy bokeh, you might be able to get away with a NIKKOR Z 180-600mm or a Sony FE 200-600mm. Otherwise, you’ll probably have to call your bank manager…!

If you’d like to order a framed print of one of my wildlife photographs, please visit the Prints page.

If you’d like to book a lesson or order an online photography course, please visit my Lessons and Courses pages.